Raphael Noz: Between the Visible and the Invisible

Originally

published as a catalog essay for Provincetown Art Association

and Museum, 1999

I met Raphael my first winter in Provincetown, back in 1993.

That winter the heavens dropped more snow than I had seen in

my whole life, and in my chilly furnished sublet on Mechanic

Street, I survived the weather and the solitude on poetry and

wine and rich conversation with a few new friends, other washashores,

dislocated, searching. Raphael was among us.

I remember the amazing story of Raphael's arrival in P'Town.

On a cold, starry evening in the winter of 1992, he crested

the last hill in Truro, and drove down into the town. He parked

his car in the town lot at the wharf, and as he walked away,

he noticed the license plate of the car in front of him. It

read NOZ. Raphael is deeply drawn to such mysterious synchronicity.

In the work exhibited here, he is moving through that darkened

doorway between the visible and invisible. Indeed, the work

in this exhibition might be considered a kind of spiritual

practice, for he is exploring the unexplainable, the inexpressible,

the sacred context of our lives. Getting to this place has

taken courage.

Born in Los Angeles in 1964 to a Mexican father and an American

mother, later separated, Raphael grew up in the white world

of West LA. His father spoke little of his family or his Hispanic

heritage. Raphael lived with that mystery. He left the city

for college in Washington State, then traveled to Italy to

study in Florence. Later Raphael moved east to study at Rhode

Island School of Design and the Museum School in Boston. At

28 he came to Provincetown where, he says, he grew up. Years

later, a friend asked Raphael for a favor. Would he bring

a family

heirloom up to Boston for him, a portrait of

the friend's deceased father? Raphael traveled to Boston to

deliver the portrait. Later he found out that in that same

period of time his own father had died. He went home to Los

Angeles for his father's funeral. There spent time with half-siblings

from his father's first marriage, whom he had never met…full

Hispanic siblings, with his own brown skin and eyes. "I

saw I was more like them than the family I had grown up with." It

was a catalyst for him to seek out his heritage. He decided

to go to Mexico. He would take with him the watches, found

with his father's things. The alarm on one of them kept going

off. He would give the watches away, to the street children,

and lay his father to rest. The prospect of the journey was

terrifying. He had the overwhelming feeling that this was a

death trip -- “I was sure I was going to die." Still,

he went to Mexico. And that pilgrimage, returning the father

to his home, "gave birth to me." In that transforming

experience, Raphael located his native, visual language.

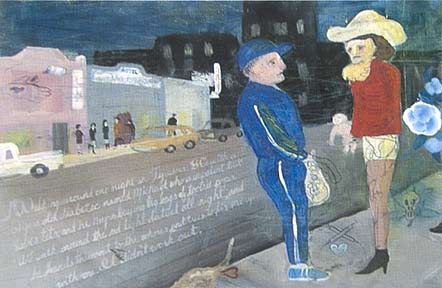

Painting on metal, Raphael expands on the Mexican tradition

of ex votos, or prayer painting. Ex votos are story pictures,

which are created out of thanks for a special happening or

intervention, often incorporating text as a way of making the

message more explicit. Raphael transforms his experience and

personal memories into visual narratives, turning his own life

history into small universal testaments to the presence of

the unexplainable in our daily lives. Larger than any human

conception, in the midst of dislocation, loneliness, fear,

love, desire, family ties, there is the intangible, the inexplicable.

In the hidden lies the power.

These

paintings breathe the sensation of place and feeling. In

The Two Dollar

Bill, a brown hand appears in the corner,

reaching from the last pew of small, sparsely peopled sanctuary

at St. Peter's to drop a two-dollar bill in the collection

plate, while in the background, the space diminishes to the

altar mural. The mural depicts Jesus' calling of St. Peter.

We don't see the subject, the "I" of the painting,

only the brown hands and the text, written in a child's awkward

cursive, in the prayer missal he holds. It is a message from

his father: Sure, I'd love to visit Cape Cod. It's ok to let

me go. It's ok to have your own life.

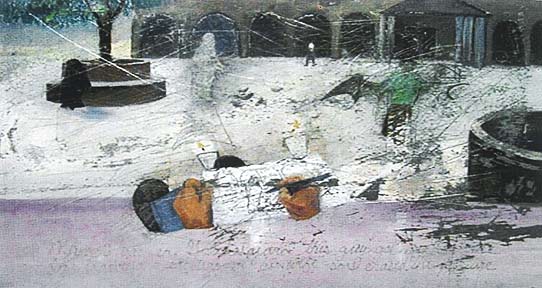

The paintings carry the distressed look of relics, a kind

of defaced elegance. Like an old colonial capital, like the

Mexico City of the 30's and 40's remembered by the Mexican

poet Octavio Paz:

I loved everything about that city, even though it had an

air of fallen

greatness. Today we often sigh when we think

about the Mexico of

those years, but it already showed signs

of a beauty mistreated.

Something which had seen better days.

Poverty and greatness:

an old grandeur and a sense of melancholy.

To

achieve this effect, Raphael often leaves the pieces outside,

exposed to the dirt and settling dust of the city, to the humanness

of the city. "It is better," he says, "to stay

close to the dirtiness. Dirtiness and elegance co-exist. That's

life."

Raphael sometimes shops for his subjects in the marketplace

of Mexican history. The newest pieces in this exhibition grow

out of contrasting images from the colonial period, when his

Spanish ancestors immigrated to Mexico, when European cruelty

and civility encountered indigenous Indian culture. Like traditional

ex-votos, these paintings carry a vocabulary of images, a conciliatory

iconography, deftly uniting opposites. It is that point of

encounter, the intersection of the sacred with the profane,

the refined with the primitive, the masculine with the feminine,

the conscious with the unconscious, all existing at the same

time that ignites Raphael's imagination.

Several works are shaped like vessels. These pieces are often

decorated with finely rendered figures and carefully crafted

attachments, a form which combines the peasant tradition of

hammered metal decoration and European style painting. Some

vessels carry a religious symbolism, like the ritual chalice

offered during mass. One piece presents a celebratory vessel,

with a womb-shaped frame, opening on a family portrait - the

child's christening. Campaign, shaped like a gushing heart,

depicts the Spanish soldiers riding to battle the Indians.

The Night Sea holds the image of a thoroughly modern buff guy

in a thong, headless, levitating over the green sea. Above,

the animate moon and stars, observing all, suggest a benevolent

presence.

The paintings in this exhibition tell us of the power of hidden

things. It is Raphael's obsession, to pursue the ultimately

futile work of trying to describe the invisible. In a way,

he says, he can only fail. Yet he persists, the hope of rebirth

in the doing.

|